Lucy Fenwick arrived in Greyharrow on the last bus before dusk—if the word “town” could still be used for a handful of leaning cottages, a shuttered post office, and a church whose steeple listed like a drunk testing the wind.

The air smelt of salt and wet stone. Mist drifted through the lanes in slow, deliberate folds, as though the sea itself were breathing onshore.

She stepped onto the gravel verge with a single rucksack and the feeling—persistent, irritatingly fragile—that she had outrun something. Not escaped precisely. Just… outpaced it for a while.

Greyharrow didn’t bother greeting her. It watched instead, the way animals do when they haven’t decided whether you’re prey or kin.

The rector, Father Elias Curnow, was waiting outside the lychgate, clutching a lantern whose glow fought a losing battle against the rising fog. He was tall, stooped, with a beard like driftwood and eyes that seemed older than the parish itself.

“You must be Lucy,” he said, voice gentle but carrying the unmistakable gravity of someone who had buried more parishioners than he’d baptised.

She nodded. “Thanks for letting me stay.”

“You wrote that you needed quiet. Greyharrow has that in abundance. Perhaps too much.”

He offered no smile to soften the words. Instead, he gestured for her to go through the gate. The churchyard grass slicked her boots, beads of moisture rolling off like cold sweat. Beyond the church loomed—a patchwork of centuries, walls freckled with lichen pale as bone dust.

Inside the rectory kitchen, the kettle hissed, and Elias poured her tea with unexpected ceremony, as if performing a sacrament. Lucy wrapped her hands around the hot mug, willing the warmth inward.

“How long do you intend to stay?” he asked.

She hesitated. “I don’t know. Just… long enough.”

“Long enough for what?”

“To feel like myself again,” she lied.

Elias accepted the answer without challenge. That somehow unsettled her more.

He showed her to the guest room—simple, clean, smelling faintly of lavender and old books. A single window overlooked the wetlands behind the church, a sprawl of reeds and black water that reflected the bruised sky in broken pieces.

“Stay clear of the marsh after dark,” Elias warned. “The tides are unpredictable. Even locals lose their way.”

She nodded, but the view tugged at her. The wetlands of Southwest England were beautiful in a bleak, ancient way—like a wound that had never quite healed over.

After unpacking, Lucy wandered outside. Greyharrow’s paths were narrow, knitted between stone walls that crumbled if you looked at them too sternly. Every house had windows like watchful eyes. Curtains shifted as she passed.

At the edge of the village, a weather-scoured sign leaned in the mud:

NUMIEL’S FEN — KEEP TO MARKED PATHS

The wind rattled it like a warning whispered a little too late.

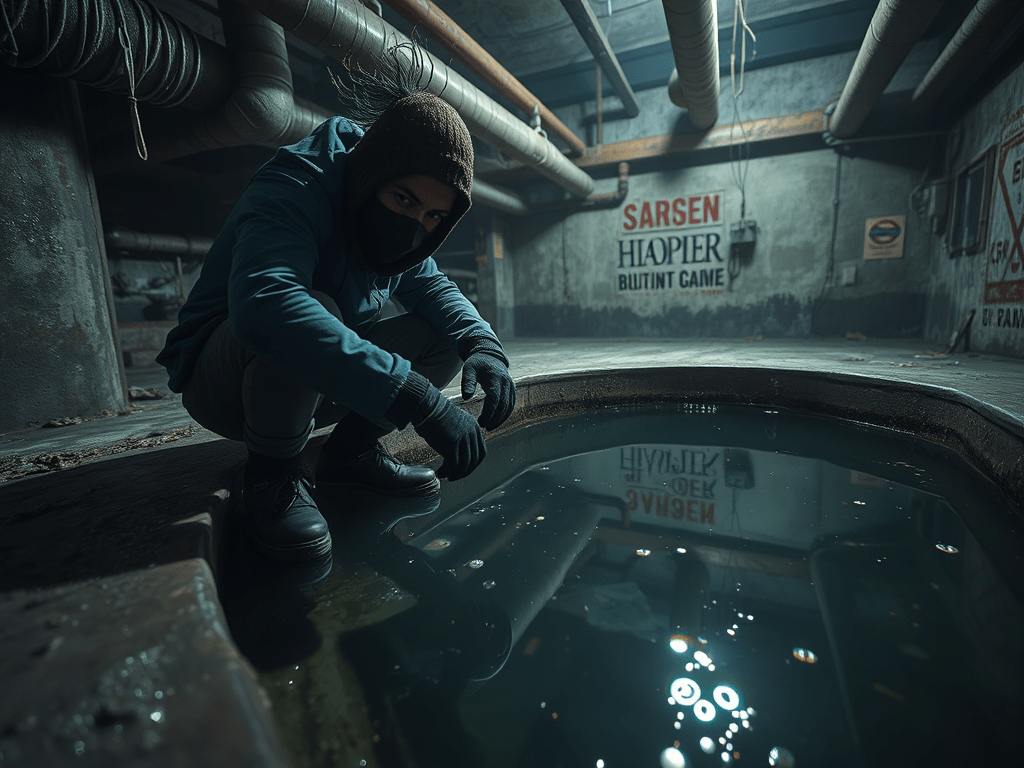

Lucy walked to the fen’s boundary. The land dipped into a labyrinth of channels—water the colour of old tea, reed beds whispering secrets in a voice just too low to decipher. Mist clung low, drifting with purpose, coiling around her boots before rolling back into the marsh, as though tasting her and deciding she wasn’t ripe yet.

She shivered.

A sound rose—something between a sigh and a distant hum, or perhaps the marsh shifting in its sleep. It reminded her of the old world she’d tried to leave behind: the hospital corridors, the whispered accusations, the hands that had shaped her fear.

She turned back before full dark.

At supper, Elias avoided small talk entirely. Instead, he asked:

“What drew you here, Lucy? People don’t find Greyharrow by accident.”

She paused, spoon halfway to her lips.

“Do you believe wounds change people?” she finally said.

His eyes sharpened. “Change is inevitable. But change without guidance…” He looked toward the window where the marsh glimmered faintly, swallowing moonlight. “That can become something else.”

Lucy didn’t ask what he meant. Something in his tone suggested she already knew.

***

That night, she dreamed of water rising beneath the floorboards. It filled her lungs gently, almost tenderly, as though teaching her to breathe a new way. In the dream, she wasn’t afraid. She opened her mouth wider.

When she woke, her pillow was damp—not with sweat, but with the faint scent of brine.

Outside her window, the marsh exhaled, and for a moment she could swear it whispered her name.

Lucy.

***

Lucy woke the next morning with sea-taste in her mouth.

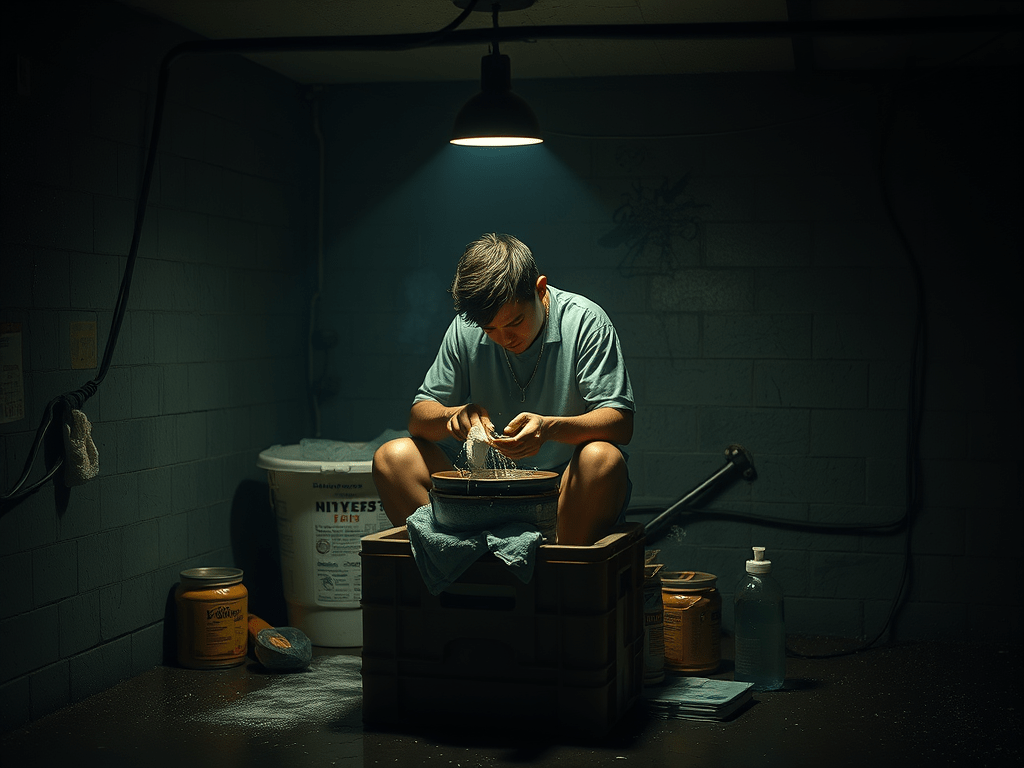

Not the clean brine of windblown spray, but something silted and stale, like the ghost of a riverbed trapped behind her teeth. She sat up too fast and the room lurched, swollen with damp despite the shut windows. Condensation had collected on the inside of the glass in perfect beads, arranged in a crescent shape—as though a wet fingertip had traced the outline again and again while she slept.

She wiped it away and told herself she must’ve done it. Sleepwalking, maybe. She didn’t remember much of the night except a rhythm—like someone knocking softly on the walls of her skull from the inside.

Downstairs, Rev. Martin was already in the kitchen, stooped over a kettle that hissed as though offended by being boiled. He gave her a smile too thin for his face.

“Rough night?” he asked.

“How did you—?”

“You look as though the sea kept you,” he said gently, pouring tea. “That happens to visitors. And to the wounded.”

Lucy bristled, but he offered her the mug with both hands, like a peace gesture. She took it.

“Your parishioners,” she said after a moment. “They… stared.”

“They stare at everyone. It’s a habit of lonely people.” He sat, shoulders sinking with the chair as though gravity was heavier on him than others. “They’re not cruel. Just… unpractised at kindness.”

“They felt like a single person,” Lucy said quietly. “As though they were all thinking the same thing. Or waiting for someone.”

The vicar’s eyes flickered, but he didn’t look away.

“They’re afraid of losing what little binds them together.”

“And what binds them?” she pushed.

He folded his hands. “Memory. Grief. The shape of absence.”

Lucy stared into her tea. A tidemark ribbon of darker brown curled inside the cup—thick, deliberate, almost like a script she couldn’t quite read.

Rev. Martin cleared his throat. “There’s a place you might like to see. If you’re strong enough today.”

She looked up sharply. “Why would I not be?”

“Because the land here remembers what happened to it. And sometimes it asks visitors to remember with it.” He stood. “But you’re free to stay in and rest.”

Which was the one thing Lucy never did—rest. If she stayed still too long, her thoughts found her, and that was worse than anything another person could inflict. So she nodded and followed him outside.

***

They walked through the village—the narrow lanes, the leaning houses stitched together by salt and old grudges—toward the western cliffs. The fog from yesterday had cleared, but a strange clarity hung in the air, as if the light came from below rather than above.

Seagulls rode a thermal high above them, but they weren’t calling. Lucy noticed the silence; the absence hung like a missing note.

“When does the tide come in?” she asked.

“In this place,” he said, “the tide isn’t so much a schedule as a temperament.”

“That’s not helpful.”

“Neither is this land,” he said simply.

They reached a slope leading toward a cove half-eaten by rock, the sea inside it dark and unusually still. A small stone chapel squatted on the sand like a barnacle that had refused to let go.

Lucy slowed. The air thickened with the scent of kelp and something sweeter—almost floral. It reminded her of hospital flowers left too long in water.

“What is this place?” she asked.

“A ruin,” the vicar said. “Older than the church. Older than the village. Possibly older than the cliff it stands on.”

“People worshipped here?”

“They mourned here,” he corrected. “Long before Christianity reached the coast. Long before anyone wrote the name of this land.”

Her skin prickled. “Mourned what?”

“Everything.” The word dropped like a stone. “But mostly the sea’s hunger.”

A shiver passed through her, sharp as a wire pulled tight.

As they stepped inside, Lucy felt the temperature drop—not cold exactly, but a hushed stillness, as though the air here had never completely exhaled. The chapel’s walls were etched with looping patterns, softened by centuries of salt-wind until they resembled the growth rings of drowned trees.

She reached out, tracing a swirling line. It was warm. Alive-warm.

Rev. Martin watched her quietly. “It listens to people like you.”

“People like me?”

“Hurt people.” His voice was gentle but firm. “People, the world has taken from. The sea knows that hunger. It recognises its own.”

Lucy pulled her hand back, throat tightening. “I don’t need to be recognised. I just need to leave.”

But the moment she turned toward the door, she saw something etched on the threshold—not new, but freshly uncovered. A sigil she’d seen before.

From her dream two nights ago.

A ring of eight crescents, each curling inward. A symbol of return. Of folding memory back onto itself.

She stepped back, bumping into the vicar. He steadied her.

“Lucy,” he said softly, “this land wakes what sleeps in people. It isn’t dangerous unless you let it be.”

“You brought me here,” she whispered. “You knew this would happen.”

“I brought you because you were already being called.”

His eyes were warm, but there was a sadness behind them, like a man who had rehearsed this conversation with others and failed every time.

Lucy backed out of the chapel and into the cold daylight, breathing too fast. The horizon swam in and out of focus. She didn’t know if she was angry or terrified or both.

“Why me?” she asked.

“Because you’ve survived things that should have killed you,” he said. “And the sea likes survivors. They make strong anchors.”

“I don’t want to be an anchor.”

“Most who are chosen don’t.”

Something shifted far out in the cove—an eddy, a ripple, the surface dipping slightly inward, as though something below was adjusting its position.

Lucy turned and walked away rapidly, not waiting for him. She didn’t care where she went—just away from him, away from the chapel, away from the feeling rising in her like all her grief had been dissolved in saltwater and poured back into her veins.

She didn’t see the faint trail she left in the sand behind her.

Not footprints.

A darker, wetter impression, as though the ground was drinking her in.

***

Her legs moved before her mind caught up — fleeing instinctively, blindly.

The path should have led out toward the wetlands. She remembered the way: a broken fence, a moss-slick stile, a long strip of mud where the reeds clattered in the wind like bones shaking in a canister. She followed it. She was certain she followed it. But after twenty minutes of walking, the air grew colder, the light dimmed, and the mist thickened into soft, damp walls.

Ahead: the chapel.

The same listing stone steps.

The same crooked bell tower leaning like a dying man.

The same dark door, waiting for her like an accusation.

Her breath caught.

She turned around immediately and walked the other way.

The fog changed — not naturally, not like weather. It moved with a thoughtfulness that felt like being watched. She walked until her feet blistered inside her boots, until the scrapes on her arms burned with sweat, until she couldn’t tell if she was trembling from cold or dread.

Then she saw it again.

The chapel.

This time she heard something inside it.

Not words.

A pulse.

Slow. Organic. Like an enormous heart beneath the floorboards.

Her own answered it.

“No,” she whispered, and backed away.

This time she ran.

The mist peeled back to reveal a landscape that shouldn’t exist: a blasted moor, but its edges bled into coastal cliffs that crumbled into black-green waves. The wind tasted metallic. The sun never rose past the horizon; it stayed like a wound that refused to close.

She ran until her lungs were knives.

Until she vomited bile.

Until her vision blurred.

When it cleared—there was the chapel.

Her knees hit the ground. She screamed so hard her throat tore, but the sound died in the fog as if swallowed by something patient.

“Why won’t you let me go?” she sobbed.

Something shifted behind her. Footsteps — slow, wet, deliberate. Lucy scrambled to her feet and ran again, forcing herself through brambles that clawed her, tearing her palms as she dragged herself over a rotten fence. Her mind frayed to threads.

I’m awake. This is real.

This is a nightmare.

This is a memory.

This is a warning.

This is a calling.

She clung to each thought like a rung on a ladder, but they dissolved beneath her hands.

She found a little lane — one she recognised from childhood summers. Tarmac cracked by roots, a sagging postbox, a hedgerow that smelled faintly of honeysuckle. She laughed in relief, hysteria breaking through like steam.

She followed it.

A bend.

A familiar oak tree.

Then—the chapel.

But this time she didn’t scream.

This time she didn’t run.

She simply stared at it as something shifted inside her chest — a sensation like a door swinging open on new hinges.

She realised she wasn’t returning to the chapel.

The chapel was returning her.

Because each time she fled, something peeled away:

a hesitation,

a fear,

a scrap of her old self.

She looked down at her hands.

Longer fingers.

Bluish veins like tide-lines under the skin.

Her nails subtly hooked, as if made for catching, tearing, clutching.

When had that started?

When had her shadow begun to flicker like underwater shapes?

When had her thoughts stopped being I need to escape and begun to become I need to understand?

The bell chimed once — low, resonant, almost tender.

Lucy inhaled. Her breath was deeper than before. Too deep. Like her lungs had grown to fill a new chamber inside her. The mist no longer chilled her; it caressed her like warm rainwater.

She stepped toward the chapel willingly this time.

The door opened before she touched it.

Inside, the pulse welcomed her like a mother greeting a lost child finally returned.

She crossed the threshold and whispered, not in fear but in recognition:

“I’m home.”

And the chapel closed behind her.

***

The smell of salt rotted the cold air as Lucy left the vicarage before dawn, unable to sleep, unable to stay still. Every night the dreams grew more vivid—tides rising inside her skull, hands of water adjusting her bones like a sculptor correcting an old mistake. She could feel the change now in her joints, in the soft tissues of her throat. The villagers looked at her differently. They no longer saw a frightened outsider; they stared as though they recognised something returning to them after a long absence.

A woman at the post office crossed herself as Lucy passed along the narrow lane.

“Numiel keeps what it marks,” the woman murmured, not quite quietly enough.

Lucy didn’t respond. She didn’t trust her voice anymore. Some mornings she sounded like herself; some mornings she sounded like the tidal drones she heard at night beneath her floorboards—low, slow, patient. A language of drowned things.

She knew the vicar, Father Elias, was watching her too, though he pretended otherwise. He followed her with gentle concern, the sort he had shown since the night she arrived half-broken and shivering on his doorstep. But lately his concern had become tinged with a resigned fear.

She noticed the way he flinched when she touched his arm.

Even he could sense the undertow.

***

The village had always belonged to Numiel, though locals hardly spoke of it anymore. They treated the sea-mist like an inheritance of grief: expected, unexamined, oppressive in its familiarity.

But Lucy felt its mechanics.

When she walked the shoreline at dusk, the mist thickened in response. Birds fell silent. The reeds bent toward her ankles as though listening for instruction. Even the ruined monastic stones—black with cold lichen—seemed to shift, aligning themselves at new angles only she could perceive.

She understood then that Numiel was not simply a “god.”

It was a system—an ancient, half-forgotten ecology of memory, loss, and reclamation. A drowned archive that fed on the experiences of those who carried unbearable trauma. It whispered to such souls. Drew them. Softened them. Hollowed them. Filled the husk with something brine-lit and patient.

Every act of violence in Lucy’s past—every humiliation, every bruise, every year of being whittled down—had been a summons.

She had come to this village because something older than pain had claimed her.

And now it wanted its due.

***

The changes began subtly: her appetite vanished; her dreams bled into waking; her reflection fogged even the clearest glass as though her breath came from deep underwater.

But soon, subtlety vanished.

Her eyes developed a ring of tidepool green.

She could see in low light.

Night no longer frightened her; in fact, darkness steadied her thoughts, sharpening them into crystalline strands.

The villagers, sensing the shift, retreated into private rituals. Doors were shut, curtains drawn. Those who dared approach her did so only to leave small offerings on the path—dried sea lavender, polished driftwood, beads carved from slick black stone.

One old fisherman bowed when she passed him and whispered, “Priestess.”

She felt no shock. Only recognition.

Father Elias saw it too. On the third night of her transformation, he confronted her in the chapel, trembling.

“You’re changing, Lucy… and I don’t think you can stop it anymore.”

She looked at him, and for the first time, felt a brief stab of pity. He was kind. He had tried. But he was part of the old order—the brittle world where suffering was endured, catalogued, moralised.

Numiel had no such illusions.

Numiel accepted the truth: to those to whom evil is done, they often become the vessel that returns it.

“I’m not afraid,” Lucy said.

“I am,” he whispered.

***

The sea-mist grew heavy that night, rolling into the village in slow tidal waves. Houses vanished. The chapel bells moaned though untouched. Lucy felt her feet moving of their own accord, leading her to the ruins by the cliff’s edge.

Father Elias followed at a distance, calling her name, his voice muffled by the fog—like someone shouting through water.

At the cliffside shrine, the stones rearranged themselves—subtle shifts, groaning pivots—forming an aperture. A mouth. A threshold.

And from it emerged the Limb of the Mother.

It was not a creature, nor a body part, nor anything that belonged to the clean categories of land-dwellers. It resembled a pale, elegant arm made entirely of tidal geometry—seafoam nerves, muscle woven from abandoned grief, joints made of polished bone and barnacle. It extended toward her with a tenderness that felt like absolution.

Lucy stepped forward without hesitation.

This was the culmination of her metamorphosis.

Not an ending—an arrival.

Behind her, Father Elias finally reached the shrine, panting, soaked with fog.

“Lucy—don’t!”

She turned to him slowly. For a moment her old self surfaced—broken, frightened, the girl who had run from danger only to carry it inside her.

But then the tide inside her surged, cold and absolute, and the last vestiges of who she had been washed away.

“The Mother requires an offering,” Lucy said—not as a request, but as a declaration of cosmic law.

Father Elias stared at her, tears gathering.

He had always known this day would come.

The villagers had said it for generations: when Numiel marks someone, the priest must be ready.

“I understand,” he whispered.

He approached her with reverent calm, kneeling on the slick stones. “If this spares the village… if this completes what began with your suffering… then let me give myself freely.”

His surrender struck Lucy deeper than any plea would have. She placed her transformed hand upon his brow; her fingertips were cool, almost translucent, marked with faint branching patterns like tidal glyphs.

“You go willingly,” she said.

“For you,” he answered. “And for whatever you become.”

The Limb of the Mother curled around him, gentle as an embrace.

Then—swift as a plunge—the shrine opened, and he was pulled beneath the stones into the drowned memory where sacrifice became nourishment.

He vanished with barely a sound.

Lucy did not cry.

Instead she stood taller, feeling her new bones settle into their ordained geometry. The mist parted around her, bowing.

She was the Priestess now.

Numiel’s mouthpiece.

The one who would carry the drowned memory into waking soil.

What the villagers feared had already come to pass.

Lucy had been running from her past, but in doing so she had become something older, deeper, patient and predatory. A worse thing than anything that hurt her.

Yet in her heart, she felt peace—cold, eternal, and utterly beyond forgiveness.

She turned to the village lights below, dim and shivering through the fog.

The tide was coming in.

And she would be its herald.

Alternate ending:

The sea-mist pressed in, thick as wool, swallowing the village behind Lucy. Stones shifted beneath her boots as she reached the cliffside shrine, the air vibrating with a low, tidal hum. The ruined stones groaned, rearranging themselves into a gaping aperture—a mouth, a wound in the world.

From the darkness, the Limb of the Mother emerged: pale, jointed, glistening with brine and sorrow. It beckoned, not with menace, but with a tenderness that made Lucy’s heart ache.

Behind her, Father Elias stumbled into view, his lantern’s glow barely piercing the fog. “Lucy—please!” His voice cracked, raw with fear and love. “You don’t have to do this. You are more than what’s been done to you.”

Lucy’s breath hitched. For a heartbeat, the tide inside her faltered.

Memories surged—hospital corridors, whispered accusations, the warmth of Elias’s hand steadying hers on that first night. She wanted to run, to scream, to beg for her old life back. But the mist pressed closer, cold and electric, and the Limb’s song filled her skull.

The ground trembled. Down in the village, lights flickered. The houses seemed to lean toward the cliff, as if the whole of Greyharrow was holding its breath, waiting for her choice.

Elias knelt, tears streaking his cheeks. “If this will spare us—if this will free you—let me give myself freely. But choose, Lucy. Don’t just surrender.”

Lucy’s hands shook. She looked down—her fingers were longer, webbed with faint blue veins, her nails hooked like a wader’s claws. She was changing, and the last scraps of her old self clung to her like seaweed.

She stepped forward, every muscle screaming in protest and longing. “I don’t want this,” she whispered, voice thick with salt and grief. “But I can’t turn back.”

The Limb enfolded Elias, gentle as a mother’s embrace. Lucy pressed her transformed hand to his brow, feeling the last warmth of her old life slip away. The shrine yawned open, and Elias vanished beneath the stones, his sacrifice swallowed by the drowned memory.

Lucy did not cry. Instead, she stood taller, feeling her new bones settle into their ordained geometry. The mist parted around her, bowing. She was the Priestess now—Numiel’s mouthpiece, the village’s doom and salvation.

As the tide roared below, Lucy turned to the shivering lights of Greyharrow. The wind carried her voice, deeper and stranger than before: “The tide is coming in. I am its herald.”

And the sea answered, rising to claim what was owed.

The sea-mist pressed in, thick as wool, swallowing the village behind Lucy. Stones shifted beneath her boots as she reached the cliffside shrine, the air vibrating with a low, tidal hum. The ruined stones groaned, rearranging themselves into a gaping aperture—a mouth, a wound in the world.

From the darkness, the Limb of the Mother emerged: pale, jointed, glistening with brine and sorrow. It beckoned, not with menace, but with a tenderness that made Lucy’s heart ache.

Behind her, Father Elias stumbled into view, his lantern’s glow barely piercing the fog. “Lucy—please!” His voice cracked, raw with fear and love. “You don’t have to do this. You are more than what’s been done to you.”

Lucy’s breath hitched. For a heartbeat, the tide inside her faltered. Memories surged—hospital corridors, whispered accusations, the warmth of Elias’s hand steadying hers on that first night. She wanted to run, to scream, to beg for her old life back. But the mist pressed closer, cold and electric, and the Limb’s song filled her skull.

The ground trembled. Down in the village, lights flickered. The houses seemed to lean toward the cliff, as if the whole of Greyharrow was holding its breath, waiting for her choice.

Elias knelt, tears streaking his cheeks. “If this will spare us—if this will free you—let me give myself freely. But choose, Lucy. Don’t just surrender.”

Lucy’s hands shook. She looked down—her fingers were longer, webbed with faint blue veins, her nails hooked like a wader’s claws.

She was changing, and the last scraps of her old self clung to her like seaweed.

She stepped forward, every muscle screaming in protest and longing. “I don’t want this,” she whispered, voice thick with salt and grief. “But I can’t turn back.”

Elias’s voice softened, almost reverent. “You were never meant to turn back. None of us do, not really.” He reached for her hand, and as their skin touched, Lucy felt a jolt—recognition, ancient and electric. “I was chosen once, too. Long ago. I resisted, and the village suffered for it. I’ve waited for someone strong enough to finish what I could not.”

Lucy stared at him, horror and understanding dawning together. “You brought me here.”

He nodded, shame and hope warring in his eyes. “I guided you, yes. But only because the cycle must end. You can break it, Lucy. Or you can become what I could not.”

The Limb of the Mother hovered, patient. The mist thickened, pressing against Lucy’s skin, urging her forward.

Lucy’s choice was no longer just about surrender or survival—it was about ending the cycle, or embracing it fully. She looked at Elias and saw the weight of years, the scars of regret. She saw herself reflected in him, and in that moment, she understood: the true offering was not just a sacrifice, but a reckoning.

She pressed her transformed hand to Elias’s brow, feeling the last warmth of his old life slip away. The shrine yawned open, and Elias vanished beneath the stones, his sacrifice swallowed by the drowned memory. But as he disappeared, Lucy felt the cycle break—a thread snapping, a tide receding.

She stood taller, feeling her new bones settle into their ordained geometry. The mist parted around her, bowing. She was the Priestess now—Numiel’s mouthpiece, the village’s doom and salvation. But this time, she was not just a vessel. She was the breaker of chains.

As the tide roared below, Lucy turned to the shivering lights of Greyharrow. The wind carried her voice, deeper and stranger than before: “The tide is coming in. I am its herald. But the tide will turn.”

And for the first time, the sea answered with silence—a promise of change.

© B. C. Nolan, 2025. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment