Curated by The House of Veyne, Londinium

Few artists working today dare to approach the body not as subject but as medium. Wyndham Blake does more than dare — he insists. His work is neither mere provocation nor morbidity, but a confrontation with the limits of material, identity, and mortality.

Blake was born in Wyndham (from which he takes his chosen name), though his early life remains enigmatic. What is known is that his art arose in the aftermath of the Thelemic currents that reshaped our century. Where others saw disaster, Blake saw canvas. His practice takes skin — stretched, treated, and marked with sacred inks — and transforms it into an archive of human experience. Each pore, each hairline fissure becomes a site of inscription.

To stand before a Blake is to feel one’s own flesh reflected, even implicated. Viewers frequently report the uncanny sensation that his works “breathe” or “follow” them with their eyes. Blake himself has dismissed such accounts as “a natural response to materials that mirror us too closely.”

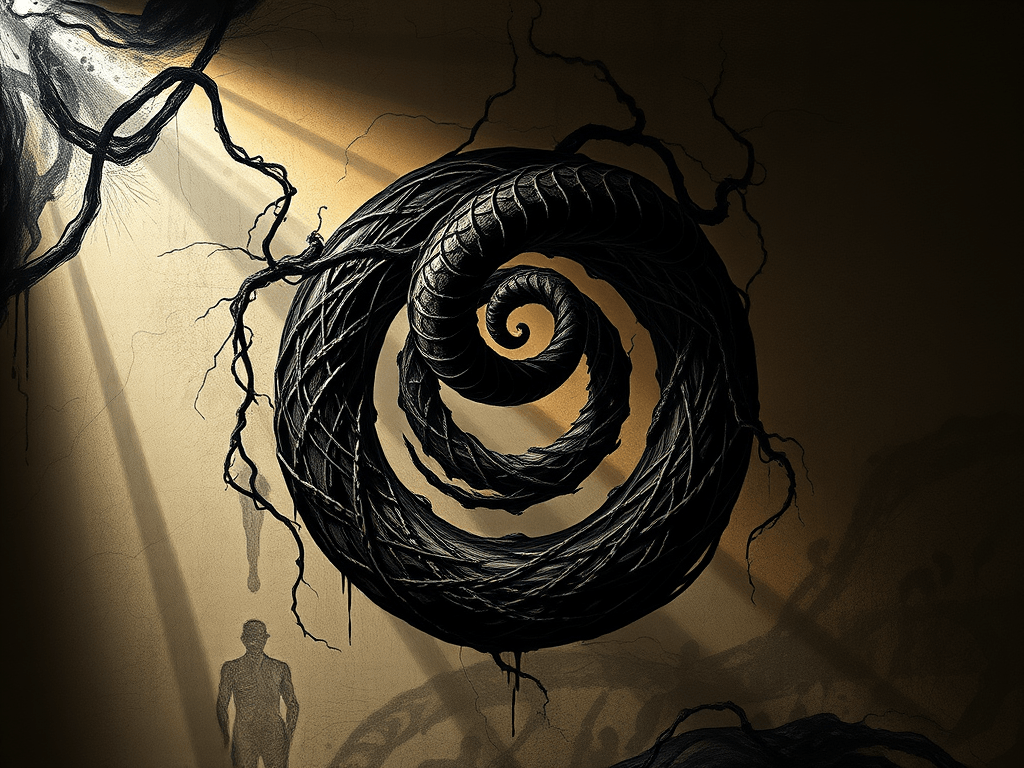

The series exhibited here, The Flesh as Icon, moves beyond representation into revelation. From the ouroboros of Self-Consumption, to the tattooed landscapes of Eden / Skin No. VII, Blake charts a theology of the body — a liturgy written in tissue. These are not allegories but relics, and in their presence, the distinction between subject, object, and observer collapses.

Blake is not a painter of death, but of continuation. His works remind us: the body is never finished, only transferred. In his own words:

“The canvas looks back.”

***

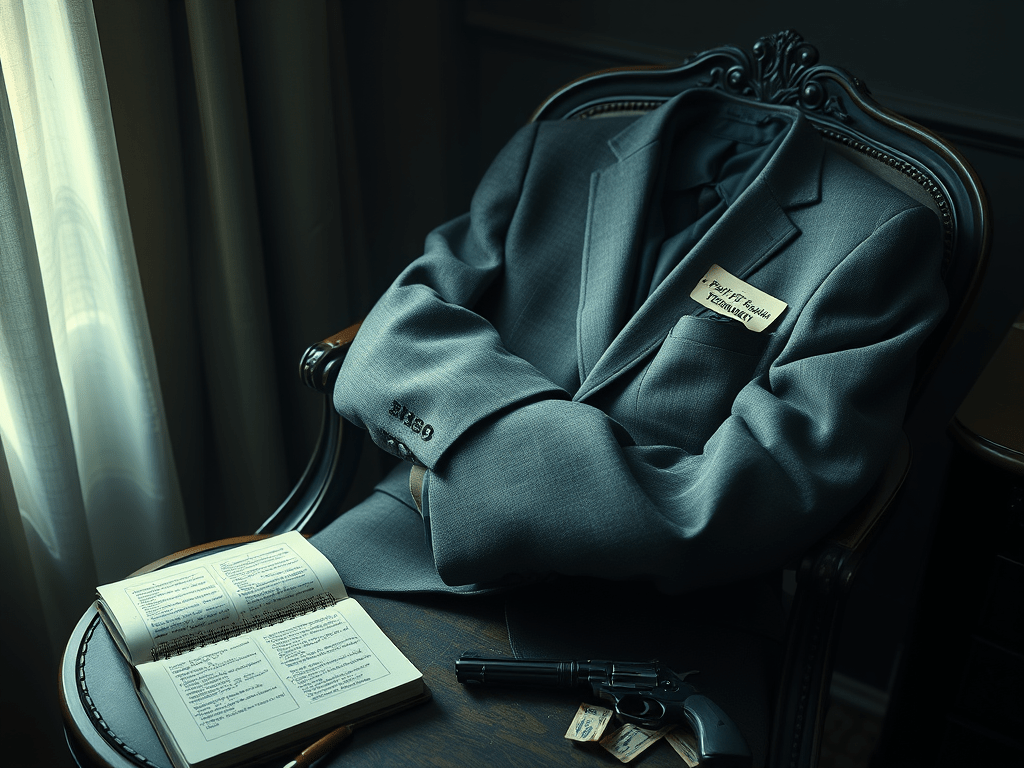

The exhibition was private, invitation-only, and the lighting had been curated to flatter both the paintings and the patrons. Glasses of wine were already sweating on silver trays, the quiet shuffle of tuxedos and silks filling the air with the muted theatre of wealth. A placard at the entrance declared the name in crisp serif: WYNDHAM BLAKE.

The couple paused at the first piece.

An ink drawing, deceptively simple: two carpets overlapped, their patterns bleeding into one another in impossible tessellations. The husband nodded approvingly—geometry always soothed him.

The next: a dragon swallowing its own tail, an ouroboros rendered in black wash. The scales were so fine they seemed to ripple when one shifted their gaze.

They drifted on.

A grim figure in oils: the Reaper, draped in ash-white robes. But his scythe was bent, wrong, its blade sunk into the canvas like it had cut through not paint but some deeper membrane.

The wife lingered, frowning. “It moves,” she whispered. Her husband chuckled, too polite to agree.

Further along—things shifted. No longer allegory or myth, but fever. Beasts without names, mouths flowering across their own bodies, their eyes wet and too alive. The brushwork was exquisite, but the shapes… the shapes suggested things that shouldn’t be.

She leaned close to one canvas. Was that—? A nipple, yes, an unmistakable pink bud of flesh peeking through the storm of ink. She straightened, unsettled. Her husband was already at the next painting.

A triptych loomed. The Garden of Heavenly Delights, copied faithfully at first glance, yet in the details corrupted—tiny ears sprouted from trees, nostrils flared across the sky, the landscape itself breathed. They both felt it, the wrongness, like a held breath just behind their own.

The wife’s mouth was dry. The Garden of Eden followed, but divided down the middle: stitched together crudely, one side dominated by a spread of feminine folds, rendered too realistically, the other marked with engorged protrusions, genitals suspended grotesquely in ink. The seam between them wept dark stains.

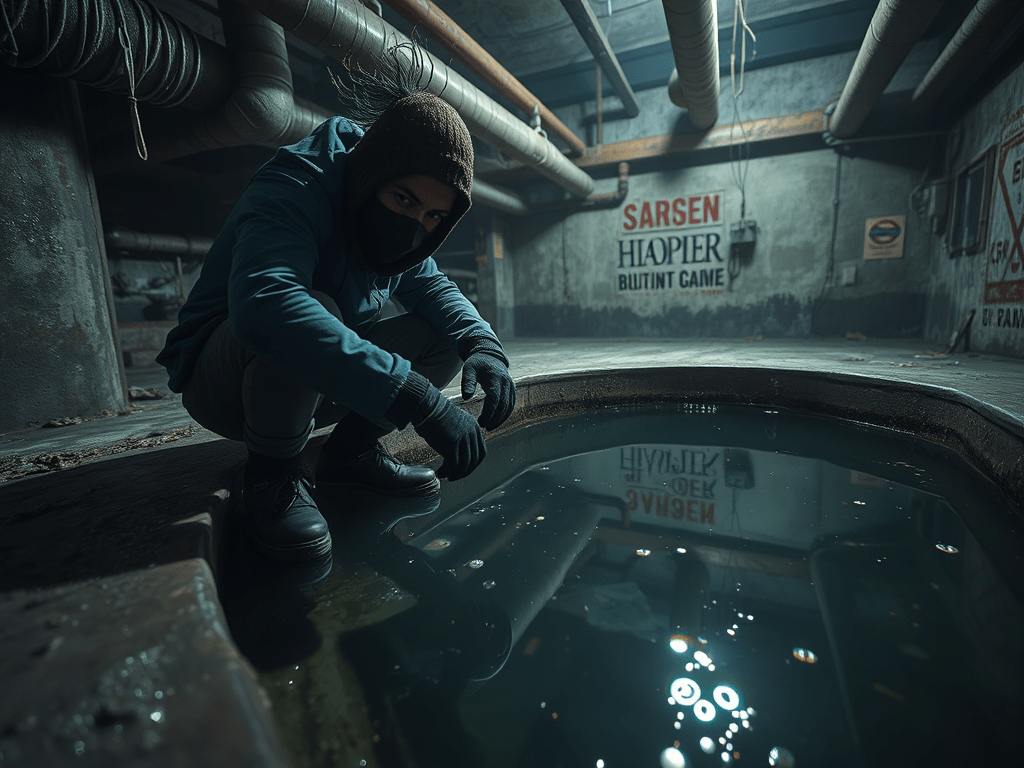

It was then they realised the texture was not canvas at all. The surfaces glistened faintly, stretched, tattooed in inks that seeped into pores. Human skin, flayed, dried, preserved. Framed.

The gallery had grown too quiet. The other billionaires still walked slowly, reverently, as though none of them dared to name what they were seeing. The couple looked at each other. Their smiles were brittle.

And yet—they did not leave.

***

The wife stepped back from the stitched Eden. The seam seemed to pulse, like breath caught beneath the surface. She swallowed, fixing her eyes on the neat brass plaque: Eden / Skin No. VII.

Her husband laughed too loudly, covering his unease. “Provocative,” he muttered, as though the word excused everything.

But she wasn’t listening.

The painted iris in one corner—a faint, almost accidental swirl of brown ink—shifted. It tracked her, just for a heartbeat, then stilled.

The wine in her hand trembled.

At the far end of the gallery, another collector was staring rapt at the Garden of Heavenly Delights. His lips moved faintly, whispering something as though in prayer. His hand lifted, unbidden, to his own ear. The wife saw why: on the canvas, one of the ears sprouting from the painted tree was the same shade, the same folded curve as his own.

The husband turned to guide her onward, but froze. A monster in the next frame—a Lovecraftian thing of tendrils and teeth—had a mole above one of its mouths. The same mole on his neck, hidden usually by his collar.

She gripped his arm. “Did you—?”

But the words died. The stretched surface of skin in the painting quivered, pores opening like pinholes. For an instant, the pores were breathing.

They both stepped back.

And then—applause. Somewhere in the hall, someone was clapping, slow and deliberate, as though a performance had just concluded. But there was no stage, no performer. Only Wyndham Blake’s works, each one glistening faintly in the gallery light, each one impossibly alive.

Neither of them dared to look away.

The clapping faded. The wife’s breath caught, then released in a nervous laugh. “Performance art,” she said quickly, too quickly. “That’s all this is.”

Her husband nodded, grateful for the words. “Of course. Brilliant, really. Unsettling, but… clever.” He tugged her arm. “Come on. Let’s not linger.”

They moved toward the next room, where the walls were white and sterile, holding only blank canvases. A reprieve. Their footsteps softened on the polished floor. Other patrons drifted, murmuring to each other as though nothing at all was amiss.

She risked one last glance back.

The stitched Eden hung in its frame, motionless. The seam was only paint; the eye only brushwork. The mole she thought she saw on the beast was nothing more than coincidence.

And yet — her skin prickled. Because for a moment, just before she turned away, she could have sworn the pores in the canvas had closed, like something beneath it had held its breath.

The husband pressed a glass of champagne into her hand. “You see? It’s all part of the show. Provocation. Shock. Art.”

She sipped, her mouth dry. Around them, billionaires chuckled and whispered, perfectly at ease.

The paintings did not move again.

Not once, not while they remained in the gallery.

But when they left, long after midnight, the wife glanced at her reflection in the dark window of their limousine. For the first time, she thought she saw not her own eyes, but someone else’s, watching back.

***

Review: Wyndham Blake’s The Flesh as Icon at the House of Veyne

By Cassandra Merton, Arts Columnist

There are exhibitions that delight, others that provoke, and then there are those rare events that alter the very vocabulary of art. Wyndham Blake’s The Flesh as Icon, now on view at the House of Veyne, belongs decisively to the last category.

Blake has been whispered about for years, a spectral figure in the periphery of the art world, his practice shrouded in rumour. With this exhibition, he steps firmly into the pantheon of the indispensable.

The works confront the viewer with what one hesitates to name: not merely the representation of flesh, but flesh itself. Tattooed, stretched, transformed, it ceases to be corporeal and becomes metaphysical — a text written in pores and scars. Critics may be tempted to label this grotesque. They are wrong. What Blake has achieved is closer to divinity.

Standing before his Eden / Skin No. VII, I felt not horror but awe. The stitching, the raw seam at the centre, the uncanny sense of the image breathing — these are not accidents but revelations. The piece does not depict the Fall; it is the Fall, enacted in real time upon the gaze of the beholder.

One cannot write of Blake without acknowledging the uncanny murmurs that ripple among viewers — the whispered claims of eyes that follow, of shapes that shift. Yet these are not faults. They are Blake’s genius. His art does not sit passively on the wall; it participates, interrogates, implicates. To be looked at by a Blake is to recognize the limits of one’s own skin.

The Flesh as Icon is more than an exhibition. It is a threshold. Cross it, and you will not emerge unchanged.

Blake has given us not shock, but sacrament.

***

Art or Atrocity? Wyndham Blake at the House of Veyne

By Lionel Harrington, Senior Critic, The New Criterion

One hesitates to dignify Wyndham Blake’s The Flesh as Icon with the term “art.” To step into the House of Veyne’s exhibition halls is to enter not a gallery, but a mausoleum dressed in couture — a chamber of horrors in which the wealthy sip champagne before what can only be described as desecrations.

Blake’s materials are the stuff of nightmares: treated hides, ink-stained dermis, what the catalogue euphemistically calls “human substrate.” The effect is predictably lurid. His so-called Eden / Skin No. VII presents a crude patchwork of genitals rendered in stretched flesh, stitched together as though for some obscene liturgy. I watched a woman blanch, certain she saw the thing breathe. Another man muttered that the ear in Blake’s parody of Bosch looked too much like his own. This is not art. This is pathology.

Defenders will no doubt rush to proclaim Blake a visionary — a pioneer of “Posthuman aesthetics,” a genius “writing liturgy in tissue.” What I saw was the opposite: an artist who had abandoned discipline for provocation, substituting shock for substance. The hushed reverence of his audience reveals less about the merit of his work than about the depravity of our age: billionaires eager to purchase not beauty, not truth, but the thrill of transgression dressed in intellectual finery.

One could excuse Blake if these works were satire, exposing the art world’s appetite for scandal. But they are not. They are deadly serious, and in that seriousness, they fail. The Flesh as Icon leaves one not enlightened, but contaminated.

Art once sought to elevate. Blake seeks only to remind us of the grave.

***

The Man Behind the Canvas: Wyndham Blake’s Murkier Origins

From the “Gallery Whisper” column, unsigned

Every season has its darling, and this year it is Wyndham Blake. His Flesh as Icon has been hailed as a genius by some and depravity by others, but either way, he has achieved the rarest of feats: ubiquity. No salon in Mayfair or Manhattan is complete without his name on the lips of patrons.

And yet—whispers persist.

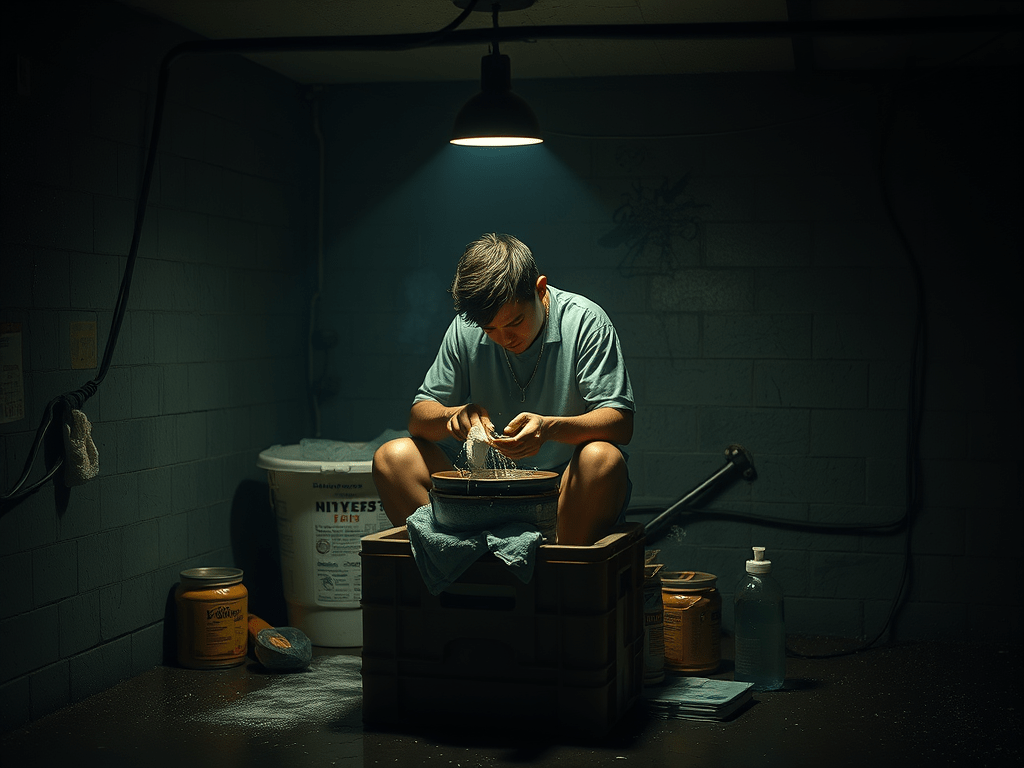

The catalogue claims Blake’s “substrates” are drawn from anonymous donors, consenting bodies, sourced ethically from medical estates. Admirable, if true. But no one seems able to produce the paperwork. No donors have come forward. No provenance is available.

A gallerist, who spoke off the record, described a private viewing some years ago. “The skin wasn’t dry yet,” they muttered, refusing to elaborate. Another collector, more candid, laughed when asked. “You think he buys it? He’s an artist. He makes it. That’s the point.”

Where Blake resides when not exhibiting remains uncertain. He is seldom seen in public, never photographed without his gloves. Those who have met him describe an unsettling presence, a gaze that lingers too long, as if studying not the face but the dermis beneath.

None of this, of course, diminishes his sales. Quite the opposite. The waiting list for a Blake grows longer with each rumour, each hushed suggestion of taboo. Billionaires thrive on what the rest of us dare not touch.

Still, the question lingers. When you hang a Wyndham Blake in your drawing room — whose skin hangs with it?

© B C Nolan, 2025. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment