The mountain did not want them there.

It made its hatred known in the slow, relentless way of something that had always existed and always would. The wind never stopped. It screamed through the passes, rattled the tents, pulled at the ropes with hands made of ice. The sky was vast and uncaring, the stars too distant to be real. There was no life here, no sound beyond the wind and the crunch of boots against snow.

Crowley revelled in it.

He stood at the edge of camp, staring up at the peaks, letting the cold burn his lungs. It was here; he thought. The thing he had come for. It was buried beneath ice and stone, waiting. He had felt it since they had begun their ascent—an unease just beyond the reach of thought, a pressure in the air, in his mind. The mountain was not simply dangerous. It was watching.

Behind him, the camp stirred. Jacot-Guillarmod was arguing with one porter, his voice sharp with frustration. The men were already uneasy. The expedition had been plagued with failure from the start—bad weather, faulty equipment, small accidents that piled up like stones in a grave. And then there was the dream.

The first porter had woken up screaming. He refused to describe what he had seen, only that it was waiting at the summit. The second had not spoken at all, just sat staring into the dark with unblinking eyes. Now the whispers were spreading. The mountain was cursed. The mountain did not want them here.

Crowley did not bother to argue. Let them feel afraid. Let them turn back if they wished. He would not.

That night, the wind shifted.

A break in the storm revealed something in the ice—a glint of black, impossibly smooth, untouched by time. Crowley saw it first, half-buried, as if it had only just risen to the surface. As if it had been waiting for them to arrive.

The porters refused to go near it. They muttered prayers under their breath, clutching their beads, but Crowley ignored them. He reached out, brushing the surface with his glove. The moment his fingers met the stone, a low pressure bloomed at the base of his skull. A sound—not a voice, not quite—a hum, resonating through his bones.

Behind him, one man let out a choked sob and turned away.

Crowley smiled.

He had found it.

*

The dead man’s mouth was still open, as if he had been caught mid-scream. His limbs were stiff, but not from the cold. Something else had passed through him, something that had left him hollow, like a husk abandoned by whatever had once made him human.

The others stood motionless, their breath thick in the freezing air. No one spoke. No one dared.

Jacot-Guillarmod knelt beside the body, his hands trembling as he reached out. “His eyes—” he whispered.

They were black. Not rolled back in death, not frozen over—just black, like something had swallowed the light inside them.

Then, somewhere beyond the wind, the whispering began.

It was faint at first, curling through the ice like distant voices carried on the storm. No words. Just sound. A hush that slithered into the ears, past the flesh, into the brain.

The porter took a step back, muttering a prayer under his breath. Another turned and fled toward the tents, but his feet tangled in the snow, sending him sprawling. His breath came in frantic gasps, hands clawing at his face like he could dig the sound out of his skull.

Crowley didn’t move.

He listened.

Something was speaking, yes—but not to them. It was not some mindless hum in the ice, nor the tortured echoes of a restless spirit. No, this was deliberate. Measured. Like an instrument, perfectly tuned to the frequencies of thought itself.

It was calling to him.

Jacot-Guillarmod let out a choked breath and stumbled to his feet. His lips moved fast, words tumbling out too quickly to make sense of them. French, then English, then something else entirely—something older, something that made Crowley’s skin prickle.

“Listen to him,” the man muttered, eyes wide with terror. “He’s—”

The doctor’s head snapped toward them, his pupils dilated. His lips still moved, but the voice that came from them was not his own.

The porter who had been praying turned and ran, vanishing into the storm. Another man took a step back toward the tents, his hand resting on the handle of his knife. Crowley saw the moment instinct overcame reason. The fear had taken hold. It would only take one man to break, to tip the rest into chaos.

Jacot-Guillarmod twitched, shuddering like a man drowning in his own skin. Then, without a word, he turned and walked into the dark.

No one followed.

The whispers grew louder.

Two nights later, one of the mutineers was found frozen at the edge of camp, his face twisted in an expression of such raw terror that even the porters refused to touch the body. Another man slit his own throat at dawn. The last of them simply stopped speaking altogether. His eyes locked on the black surface beneath the ice.

And Crowley—Crowley had never felt clearer.

The storm howled around him, but inside, his thoughts had sharpened. The weight of the world had lifted. For the first time, he could see.

This was not a curse.

Not some relic to be feared, not some artifact to be buried.

The others had been too weak to withstand it, too small-minded to comprehend. But Crowley understood. He had always suspected, had always believed there was something beyond the veil, something older than gods, older than the world itself.

And now, it had chosen him to listen.

*

Crowley had stopped counting the days.

Time had lost its meaning somewhere between the last death and the moment he realised he was the only one left. The bodies were gone now, swallowed by the storm, dragged into crevasses, or perhaps simply erased—as if the mountain had grown tired of their presence and decided to reclaim them.

It did not matter.

What mattered was the Shard.

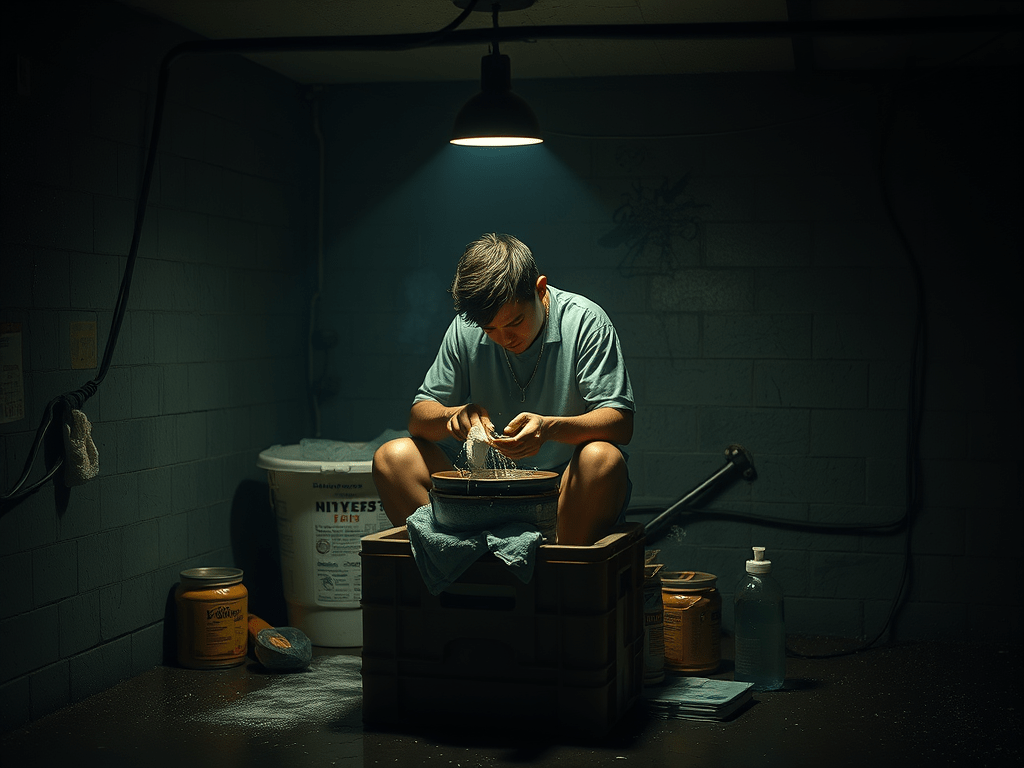

It sat before him, half-buried in the ice, drinking in the pale light like a thing alive. Black, too black—the absence of colour, the absence of anything at all. He stared into it, and it stared back. The hum inside his skull was constant now, a vibration in the marrow of his bones, a frequency that had replaced thought itself.

They had all broken in the end.

Jacot-Guillarmod had walked into the storm without a word, leaving only footprints that were gone by morning. The others had died in uglier ways—tearing at their own skin, screaming, trying to carve open their skulls as if they could scoop out whatever the Shard had put inside them. But Crowley?

Crowley had endured.

He sat cross-legged before the stone, hands resting on his knees, breath slow and measured. He did not shiver, though the cold was absolute. His mind moved in perfect clarity. The thing inside the Shard whispered to him now, no longer a hum but something shaped, something spoken.

It told him things.

It showed him the world as it truly was—not bound by order, not shackled by morality or reason, but a playground of will, shaped only by those bold enough to impose themselves upon it. It was not magic, not in the way fools understood it. It was authority, the raw ability to rewrite the rules.

That was what the others had feared.

That was why they had broken.

Crowley ran a gloved hand over the smooth, unyielding surface. He could feel the pulse beneath it, like a heartbeat made of thought itself. A circuit, a system, something old, something that had waited so long to be found again.

He would take it with him.

Not the stone itself—no, that was impossible—but the knowing. The structure it had placed inside his mind, the architecture of the great work. It had spoken through him already. He had written it in his journals, scrawled across pages in half-mad ecstasy, diagrams and revelations that made his fingers shake. But he was not mad. He was awake.

And he understood now.

It had never been about him. It had never been about any of them.

This knowledge—it was spoken.

It had been waiting for a voice.

Crowley stood, slow and deliberate, the wind shrieking around him. He turned from the Shard, from the black abyss carved into the ice, and began his descent.

*

When they found him, he was laughing.

Crowley staggered into the lower camps, half-dead from exposure, his clothes stiff with ice, his eyes burning with something far beyond exhaustion. The porters recoiled at the sight of him. His lips were split, blackened with frostbite, but the smile never left his face.

The others were gone; he told them. Lost to the mountain. His voice was hoarse, raw from the cold or from something else. He did not explain how he had survived when none of the others had. He did not tell them about the nights spent listening, about the things the Shard had placed inside his skull.

They would not have understood.

The journey back was fevered, slipping in and out of lucidity. He dreamed of structures, vast geometries that made no sense, symbols that twisted into new meanings the moment they were grasped. Sometimes, he thought he was still on the mountain, still kneeling before the Shard, the hum resonating through his bones.

He did not remember the boat. He did not remember the train. Only fragments—pages of his journals covered in ink, diagrams scrawled in candlelight, a sensation like being pulled through something not quite real.

London felt small when he returned. Flat. False.

The world had changed, or perhaps he had. The streets, the people, the very air around him—it was all painted onto something deeper, something unseen but present. The Shard had not stayed on the mountain. It had come with him. It was inside him now, speaking in the quiet moments, guiding his hand as he wrote.

This was the Work.

He did not invent Thelema. He did not create its principles. He merely translated.

Everything he had written, every revelation, every ritual—it was the echo of something older, something the Shard wanted spoken into reality.

He had glimpsed the Consensus Mechanism, the hidden system beneath the skin of the world, the architecture of thought itself. And if reality was only a construct of will, then who better to shape it?

Crowley smiled to himself, ink staining his fingers.

He had brought something back from the mountain.

And it had only just begun.

*

Cairo, 1904.

The air inside the hotel room was thick with incense and cigarette smoke. Crowley sat at the desk, pen poised, waiting for the great revelation to begin. He had prepared himself for this moment—fasting, meditating, adjusting his consciousness to be in perfect alignment with whatever Aiwass was.

But nothing happened.

No great voice thundered through the ether. No celestial force parted the veil. Instead, he heard giggling.

His wife, Rose, was mumbling in her sleep again, laughing at some drunken fool’s ramblings. Crowley scowled. She had been different ever since the pyramid visit. Talking to things unseen. Muttering cryptic nonsense. Claiming to know secrets even he didn’t.

Then the voice came.

Not from the aether. Not from beyond the veil.

From the other room.

“Alright, alright, listen—consciousness is a recursive feedback loop, yeah? The gods? Symbols—archetypes! You don’t summon them, you channel them. Like a shared hallucination, but realer than real, right? It’s all about Will—capital W, mate. That’s the trick!”

Crowley’s eyes went wide.

“Rose?” he called out. “Who the bloody hell are you talking to?”

There was a crash, followed by more drunken giggling.

“Shhh!” Rose hissed. “You’ll scare him off!”

Crowley stormed into the next room—then stopped cold.

There, slumped against a table covered in empty wine bottles, was Aiwass.

Or someone who would become Aiwass.

A tall man, dressed in strange, anachronistic robes, looking like some out-of-place hybrid of an ancient priest and a washed-up occult rockstar. His hair was a mess, his eyes far too bright, and in his hand was a cup of something unearthly strong.

He looked up at Crowley, bleary-eyed, and grinned.

“Oh. Right. “

Something clicked in Crowley’s mind, something too big to process—a spiralling ouroboros of time, where cause and effect had eaten themselves alive. Aiwass hadn’t dictated The Book of the Law.

He had just gotten shitfaced in the past, and Rose overheard him ranting about occult theory.

The realisation hit like a hammer.

This wasn’t divine revelation. It was a cosmic joke—a closed loop, where Crowley’s entire life’s work had been dictated by some drunken, time-travelling version of the very thing he was trying to summon.

Aiwass pointed a sloppy, accusatory finger at Crowley.

“You’re gonna wanna write this down, mate. It’s important.”

Crowley, reeling, staggered back to the desk, hands shaking.

He put pen to paper.

And history wrote itself.

Time did not move forward. Not for him. Not after Cairo.

The Book of the Law had written itself, dictated by a voice that was his but wasn’t—a drunken echo of something that had already happened. That would always happen. And so he played the part. The Prophet. The Beast. The Great Wild Card of the Aeon.

He performed the rituals, preached the Will, and walked the Earth like a man whose destiny had been forged in fire and forgotten in the ashes. Thelema spread, mutating and growing like a virus of the mind. He had glimpsed the Consensus Mechanism and survived, but whether he had changed it or merely acted as its instrument, he would never know.

The years were not kind. His body withered under the weight of absinthe, heroin, and unfulfilled ambition. A prophet should have died in glory, but Crowley withered away in a boarding house, impoverished and abandoned, his myth grander than the man himself.

His last words, mumbled through dying lips:

“I am perplexed.”

And then—

He awoke.

*

The bed was unfamiliar. The room smelled of damp wood and old whiskey. Crowley sat up, squinting at the ancient wallpaper peeling in psychedelic curls, at the heavy oak furniture and the dim candlelight flickering in iron sconces.

A man stood at the foot of the bed. Tall. Pale. Wearing a butler’s uniform that looked both immaculate and slightly unreal, like something lifted from an old dream.

“Ah,” the man said, in the kind of crisp, well-trained voice that suggested he’d been practicing hospitality for a very, very long time. “You’re awake.”

Crowley blinked. “Where the bloody hell am I?”

“The Boleskine Hotel,” the Butler said. “You are its new proprietor. Welcome.”

Memories swam, disjointed. Boleskine. The ritual. The Abramelin working—unfinished.

The Butler continued:

“It is a sanctuary for those who don’t belong. Daemons, misfits, lost souls. Think of it as a last stop before reality eats them whole.”

Crowley groaned and swung his legs over the side of the bed. His boots were already on. Of course they were.

“Alright,” he said. “Show me around.”

The Butler led him down twisting corridors lined with impossible doors, past a smoking lounge where ghosts argued over chess, through a bar where a man with a goat’s head sipped absinthe in silence. The air was thick with incense, cigarette smoke, and latent probability.

They stepped into the grand hall just as the window exploded inward.

A massive tentacle—slick, muscular, horrifically alive—lashed through the shattered glass, coiling around Crowley’s waist before he could react.

He screamed obscenities as it yanked him out into the night.

Then—

Silence.

A few seconds later, he was spat back through the window, soaking wet, gasping for breath, landing with a splat on the wooden floor.

The Butler didn’t flinch.

“That’s Nessie,” he said, adjusting his cuffs. “I think she likes you.”

Crowley coughed up a lungful of loch water, glaring. “What the hell is she doing here?”

The Butler arched a brow.

“Well, you didn’t finish the Abramelin Ritual, sir. So, really—it’s your bad that she’s in the loch.”

Crowley stared at him.

Then, wiping his face with the sleeve of his now-ruined robe, he exhaled.

“Right,” he muttered. “Guess I’ve got work to do.”

© Aiwaz, 2025. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment